Alignment Problems

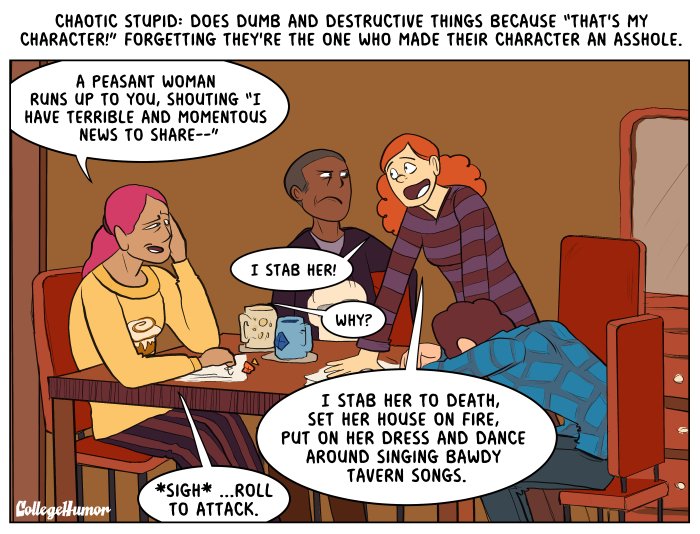

As the heroic band of adventurers prepares to confront the kingdom’s apathetic ruler and attempt to persuade him to take action, a lone figure stalks the shadows at the periphery of the throne room. The players prepare their serious, passionate, and thoughtful plea. The character sneaking closer to the throne looks to the Dungeon Master and says, “I sneak up to the king and yank his pants down to his ankles.” A collective groan issues from the rest of the party. “What?” retorts the pants-thief, “Zook Fabblestabble is chaotic neutral!”

A Heated Debate

There are few topics as hotly debated in tabletop gaming as alignment. In Dungeons and Dragons, the mechanics underpinning alignment have changed, sometimes dramatically, with each new edition of the game. An individual player’s perspective on alignment is going to be strongly influenced by how many and which specific implementations of alignment they have been exposed to. At the table, a game can be significantly disrupted when expectations and executions of alignment aren’t shared by all of the players.

The Player’s Handbook explains that chaotic neutral “creatures follow their whims, holding their personal freedom above all else.” A chaotic neutral character will act heroically only when they stand to benefit from those actions. They will not let law or tradition prevent them from behaving however they see fit. While strongly self-interested and aloof, they can easily value the friendship or respect of their adventuring companions and are fully capable of deciding to act in the interest of these relationships.

So what do you do when a player at your table thinks that the chaotic neutral, or any other, alignment gives their character the justification to act zany and random without regard for the consequence of their actions and the interests of their fellow gamers?

Talk It Out

Talk about the problems with your player as soon as you can. When you bring up the issue with the player, focus on the actions of the character and include specific examples. Avoid making assumptions about their motives as a player and make it clear that your concern is about keeping the party unified in enough of their goals that they can continue to adventure together. If you aren’t already familiar with their preferred play style, ask questions about it. If you didn’t cover alignment in your session zero (see below), ask what they know about the subject and how they decided upon their character’s alignment.

Present Alternatives

Once you have opened a dialogue with your problematic player make sure the conversations continue beyond just pointing out the troublesome behavior of their character. Work with the player to come up with alternative actions, motivations, and/or goals for their character that meets the objectives of their preferred play style and the concept of their character. This helps the player understand your expectations for acceptable and unacceptable character behavior. It might lead to the player choosing a new alignment for their character or discovering new and interesting aspects of the character’s persona. If these changes are appealing or exciting for the player, it helps keep them invested and connected to the game and solidifies their commitment to continuing to be a part of the team.

Acknowledge Play Styles

Find out what they want from the game and include that. Sometimes disruptive behavior is intended to grab the spotlight or push the game in the direction that the player is more interested in interacting with. Page 6 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide showcases many of the broad categories of player satisfaction that you can use as a reference for identifying what your players want and how to give it to them. You’ll need to be willing to consider changes to your game, but doing so has the potential to increase the fun everyone is having and minimize unwanted disruptions.

Session Zero

Understand and communicate how alignment works for your game before you start playing. Behavior that you or other players at the table find disruptive is more likely to occur if everyone isn’t on the same page about how to use alignment. At your table, alignment might be a quick description of the broad moral and social attitudes of a creature where individuals are not expected to act in accordance with their alignment 100% of the time. This is the approach taken by the current edition of Dungeons and Dragons and can be a useful tool in helping you answer questions about the outlook of your character and how they might act.

You can also borrow or adapt the approach that past editions of D&D used. Fourth edition treated alignment as a kind of cosmic allegiance that you pledged and not an indicator of your values or actions. This meant that a Lawful Good character might be a terrible individual that resorted to evil deeds to advance the goals of law and good within the universe. Even older editions of the game treated alignment as a consequence of actions that a character had taken. You might start with a Lawful Good character, but if you ignored the laws of civilized society too often the DM could direct you to change your alignment to reflect the reality of your actions. In essence, the forces of good and evil and law and chaos were fundamental properties of the cosmos that left their mark on creatures as the undertook actions associated with their traits.

All of this assumes that the player creating difficulties at your table is interested in cooperating. This won’t always happen. Some personalities have significant difficulty playing well with others and it’s okay to encourage or require such an individual to step away from your group when they’re unwilling to work with you to make changes to improve the experience for everyone playing the game.

If you’re a DM that has dealt with players causing problems because of their character’s alignment, tell us about it in the comments. How did you try to remedy the situation? Was your intervention successful?

David Adams

Part-time freelancer, full-time wizard. Works for coin or spell scrolls.

David Adams has been pestering Dungeons and Dragons publishers for the past 12 years and managed to collect a myriad of credits in that time. He has had the good fortune of seeing his content published by the likes of Kobold Press and Wizards of the Coast in addition to other recognizable companies.

David started playing D&D when he was 16 and the game has been an amazing outlet for creativity as well as a fascinating space to explore complex social issues while simultaneously slaying dragons in epic combat. The ability of the game, regardless of edition, to transmute his interests into exciting experiences he can share with friends is the key aspect that keeps his interests fixed upon it.

Alignment Problems

As the heroic band of adventurers prepares to confront the kingdom’s apathetic ruler and attempt to persuade him to take action, a lone figure stalks the shadows at the periphery of the throne room. The players prepare their serious, passionate, and thoughtful plea. The character sneaking closer to the throne looks to the Dungeon Master and says, “I sneak up to the king and yank his pants down to his ankles.” A collective groan issues from the rest of the party. “What?” retorts the pants-thief, “Zook Fabblestabble is chaotic neutral!”

A Heated Debate

There are few topics as hotly debated in tabletop gaming as alignment. In Dungeons and Dragons, the mechanics underpinning alignment have changed, sometimes dramatically, with each new edition of the game. An individual player’s perspective on alignment is going to be strongly influenced by how many and which specific implementations of alignment they have been exposed to. At the table, a game can be significantly disrupted when expectations and executions of alignment aren’t shared by all of the players.

The Player’s Handbook explains that chaotic neutral “creatures follow their whims, holding their personal freedom above all else.” A chaotic neutral character will act heroically only when they stand to benefit from those actions. They will not let law or tradition prevent them from behaving however they see fit. While strongly self-interested and aloof, they can easily value the friendship or respect of their adventuring companions and are fully capable of deciding to act in the interest of these relationships.

So what do you do when a player at your table thinks that the chaotic neutral, or any other, alignment gives their character the justification to act zany and random without regard for the consequence of their actions and the interests of their fellow gamers?

Talk It Out

Talk about the problems with your player as soon as you can. When you bring up the issue with the player, focus on the actions of the character and include specific examples. Avoid making assumptions about their motives as a player and make it clear that your concern is about keeping the party unified in enough of their goals that they can continue to adventure together. If you aren’t already familiar with their preferred play style, ask questions about it. If you didn’t cover alignment in your session zero (see below), ask what they know about the subject and how they decided upon their character’s alignment.

Present Alternatives

Once you have opened a dialogue with your problematic player make sure the conversations continue beyond just pointing out the troublesome behavior of their character. Work with the player to come up with alternative actions, motivations, and/or goals for their character that meets the objectives of their preferred play style and the concept of their character. This helps the player understand your expectations for acceptable and unacceptable character behavior. It might lead to the player choosing a new alignment for their character or discovering new and interesting aspects of the character’s persona. If these changes are appealing or exciting for the player, it helps keep them invested and connected to the game and solidifies their commitment to continuing to be a part of the team.

Acknowledge Play Styles

Find out what they want from the game and include that. Sometimes disruptive behavior is intended to grab the spotlight or push the game in the direction that the player is more interested in interacting with. Page 6 of the Dungeon Master’s Guide showcases many of the broad categories of player satisfaction that you can use as a reference for identifying what your players want and how to give it to them. You’ll need to be willing to consider changes to your game, but doing so has the potential to increase the fun everyone is having and minimize unwanted disruptions.

Session Zero

Understand and communicate how alignment works for your game before you start playing. Behavior that you or other players at the table find disruptive is more likely to occur if everyone isn’t on the same page about how to use alignment. At your table, alignment might be a quick description of the broad moral and social attitudes of a creature where individuals are not expected to act in accordance with their alignment 100% of the time. This is the approach taken by the current edition of Dungeons and Dragons and can be a useful tool in helping you answer questions about the outlook of your character and how they might act.

You can also borrow or adapt the approach that past editions of D&D used. Fourth edition treated alignment as a kind of cosmic allegiance that you pledged and not an indicator of your values or actions. This meant that a Lawful Good character might be a terrible individual that resorted to evil deeds to advance the goals of law and good within the universe. Even older editions of the game treated alignment as a consequence of actions that a character had taken. You might start with a Lawful Good character, but if you ignored the laws of civilized society too often the DM could direct you to change your alignment to reflect the reality of your actions. In essence, the forces of good and evil and law and chaos were fundamental properties of the cosmos that left their mark on creatures as the undertook actions associated with their traits.

All of this assumes that the player creating difficulties at your table is interested in cooperating. This won’t always happen. Some personalities have significant difficulty playing well with others and it’s okay to encourage or require such an individual to step away from your group when they’re unwilling to work with you to make changes to improve the experience for everyone playing the game.

If you’re a DM that has dealt with players causing problems because of their character’s alignment, tell us about it in the comments. How did you try to remedy the situation? Was your intervention successful?

David Adams

Part-time freelancer, full-time wizard. Works for coin or spell scrolls.

David Adams has been pestering Dungeons and Dragons publishers for the past 12 years and managed to collect a myriad of credits in that time. He has had the good fortune of seeing his content published by the likes of Kobold Press and Wizards of the Coast in addition to other recognizable companies.

David started playing D&D when he was 16 and the game has been an amazing outlet for creativity as well as a fascinating space to explore complex social issues while simultaneously slaying dragons in epic combat. The ability of the game, regardless of edition, to transmute his interests into exciting experiences he can share with friends is the key aspect that keeps his interests fixed upon it.

0 Comments